Eli Solt

Cinematographer

Modernity’s Sacrifice:

Pessimism and Familial Violence in The Killing of a Sacred Deer

Eli Solt

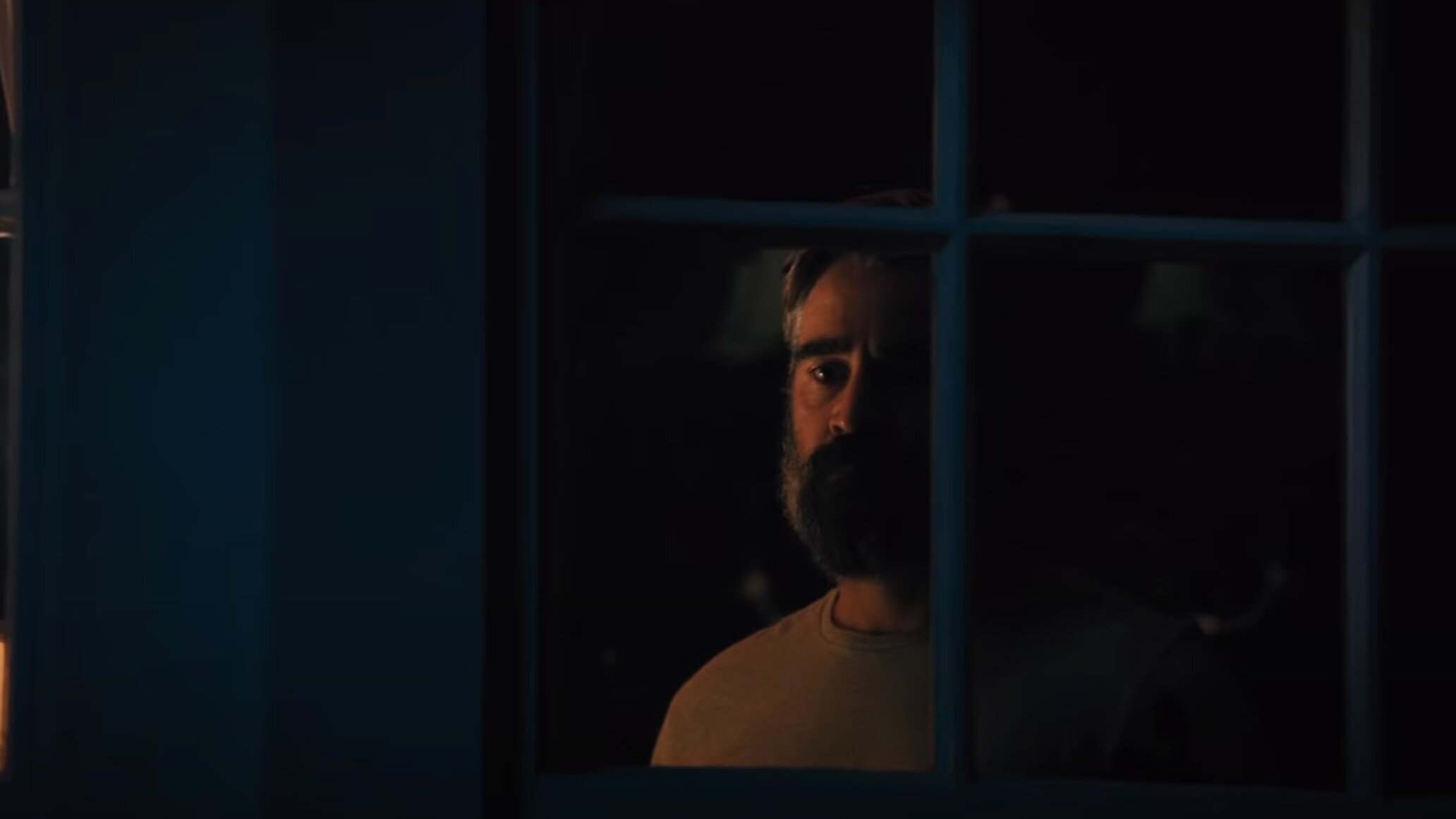

As a director, Yorgos Lanthimos is incredibly talented in his ability to manipulate his audience’s emotions to evoke intense experiences of shock and horror. His long, deadpan dialogue scenes combined with his grisly moments of familial violence evoke a sense of his own personal cynicism as he portrays a modern world that is as confusing as it is corrupt.

His 2017 film, The Killing of a Sacred Deer, perhaps represents the epitome of this auteur’s motif as Lanthimos paints a bleak and violent portrait of modern family life, our dependence on technology, and the horrifying reality of current wealth and class inequality. While formulating many of his own ideas, The Killing of a Sacred Deer is Lanthimos’ modern interpretation of Euripides’ classic tragedy Iphigenia At Aulis. Like the Greek tragedy, the 2017 film contains a plot that is structured almost entirely around the concept (and eventual action) of an intrafamilial sacrifice. After a mysterious boy named Martin reveals to Dr. Steven Murphy the supernatural chain of events that will lead to the slow and painful torture of his wife and two children, Dr. Murphy learns that the only way to prevent the agonizing deaths of all three family members is by killing one of them himself. Only later in the film is it revealed that the reason this “curse” has come across the family is because Dr. Murphy accidently killed Martin’s father in a botched surgery many years prior to the film’s events. This was due to the fact that Dr. Murphy had been drinking too much before the surgery. The death of a family member must be balanced out and Dr. Murphy must face an impossible decision. The remainder of the film (up until the scene of the sacrifice) involves Dr. Murphy’s denial of these claims, his eventual acceptance, and the long process of trying to figure out which person he should sacrifice.

While sharing many narrative and thematic similarities with Iphigenia At Aulis, The Killing of a Sacred Deer reveals some of the differences found within modern tragedy and problematizes the notion of an Aristotelian defined ‘tragic hero’. In this paper, I will focus primarily on analyzing three major scenes within the film: the opening surgery sequence, Kim’s moment of acceptance, and the final sacrificial scene. In close reading these scenes, I will compare them to Euripides’ classic play in order to reveal the similarities and differences between Classic Greek Tragedy and a similar story told in a modern context. I will argue that the roles of power and authority (both individually and societally) play major roles in the structuring of modern tragedy via frameworks of Hegelian discourses. I will also argue that Dr. Murphy does not experience a transformative character arc, unable to take responsibility of his actions, and in so doing failing to experience the emotions necessary of tragedy (pity and fear) and thus being denied of eventual character growth and catharsis. Yorgos Lanthimos’ 2017 film The Killing of a Sacred Deer further complicates the notion of modern tragedy and sacrifice by placing the act of sacrifice within a professional and societally acceptable framework and in preventing Steven Murphy from learning from his mistakes, reveals the problematic issue with the modern tragic figure.

***

The Killing of a Sacred Deer follows the story of Dr. Steven Murphy who is a well renowned cardiologist and heart surgeon. He is presented as being very wealthy as he lives in a large, clearly upper-class house with his wife, Anna, daughter, Kim, and son, Bob. Outside of work, he occasionally meets with a troubled boy named Martin, taking on a paternal role for the boy since his own father passed away. One day, Bob loses feeling in his legs and stops eating. After multiple tests at the hospital, doctors are unable to figure out what is wrong and not long after, Kim experiences the same thing. Martin then reveals that it is the beginning of a process in which each of Steven’s family members will get sick (losing feeling in lower extremities, loss of eating ability, bleeding out of the eyes, and finally death) unless he kills one of them.

While the source of Martin’s power and the supernatural curse are never explained, it becomes clear that the reason this is happening to Dr. Murphy is a punishment for his role in the death of Martin’s father in heart surgery years before. While Steven and Anna are initially in fierce denial and become angry at Martin, even reaching the extreme of kidnapping and torturing him, they eventually accept the fate of the curse and Steven must decide what to do. While his family members slowly accept reality, Steven’s inability to make a choice forces him to perform a “sacrificial ritual,” using a blindfold to randomly kill one of his family members which ends up being his son, Bob. While the final climactic sacrificial scene is one of the most important scenes of the film, the opening also features a strange kind of sacrificial scene that is important for understanding the rest of the film’s events.

Playing God

The film starts with the opening production credits followed by forty-three seconds of a completely black screen with dramatic orchestral music playing. The film then cuts to the first shot: a beating human heart. The camera begins a slow zoom out, moving upward as the aerial shot of the heart slowly reveals that the rest of the body is covered and there are doctors around performing surgery on the heart. After a minute, the shot fades to black and the title appears on screen.

This opening sequence presents a number of interesting ideas and juxtapositions that foreshadow and structure the rest of the film. First is the black screen. This opening (similar to the opening three minutes of darkness in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey) creates an unfilled cinematic space: an absence. This absence evokes a feeling of uneasiness. The music plays elegantly and dramatically and yet the audience still sees nothing. Thomas Elsaesser and Malte Hagener, in their book “Film Theory: An Introduction Through the Senses,” envision the cinema as a kind of brain. They suggest a linkage between film and spectator as if the screen represents our own vision and thoughts. With this interpretation, one could understand this opening as a representation of death. It is pure darkness; nothing. Then the film cuts into the first shot of the film which is a beating heart: life. This repositioning from death to life juxtaposes the central theme of the movie which is the act of killing or the transition from life to death. This opposition forces us to acknowledge the delicate balance between the two as we, the spectator, walk the fine line of moral ambiguity throughout the film. Opening the film in this manner also establishes the issue of Dr. Murphy’s profession, a surgeon, whose work focuses on saving lives. However, when he makes mistakes or simply because of negligence, his work can just as easily lead to death.

While the main sacrifice occurs at the end of the film, I would argue that another sacrificial ritual is taking place in this scene; a kind of sacrifice held more reasonably within the bounds of an acceptable societal framework: a failed heart surgery. The cinematography is worth noting as the shot slowly zooms out and upward, the entire scene is shot from the ceiling with a “godlike” perspective. In Rene Girard’s book “Violence and the Sacred,” he suggests that “Sacrifice has often been described as an act of mediation between a sacrificer and a “deity” (Girard 6). If we interpret the camera’s viewpoint as not literally coming from God but coming from the doctors themselves, then the doctors take on the role of God or a controlling deity. This connects with the idea that doctors “play God” as they work to keep people alive (unnaturally) or in this case, accidently let them die.

Girard continues saying, “Because the very concept of a deity…has little reality in this day and age, the entire institution of sacrifice is relegated by most modern theorists to the realm of the imagination” (Girard 6). The hyper-realistic and borderline grotesque nature of the shot (the average person is likely rarely exposed to witnessing open heart surgery) prevents the sacrificial scene from becoming fantastical or dreamlike. Instead, the realism and placement within a modern setting re-contextualizes Girard’s idea for modern sacrifice, asserting that this failed heart surgery is a form of sacrifice and the doctors performing it act both as sacrificer and a kind of deity. It also foreshadows the supernatural curse upon the family that will come later in the narrative.

The Title

After this opening shot, the title appears on screen. The text of the title uses three different fonts and styles. The words “the,” “of,” and “a” use a fancy serif font, are in italics, and are all lowercase. “Killing” uses a similar serif font (though slightly more eloquent in design) and is in all caps. “Sacred Deer” is also in all caps but is bolded and uses a very different sans serif font.

These aesthetic distinctions have several textual implications. The first is that the motif of “three” is emphasized throughout the film. There are three other members of Dr. Murphy’s family, three people he must decide between of whom to kill, and three people at risk in the final sacrifice. Characters in the film are frequently framed in “three shots” (emphasized by mise-en-scene). There are also three stages to the bodily deterioration that happens under the curse. Secondly, the changes in font evoke different psychological responses. Thomas Sanocki, in his paper “Effects of Font- and Letter-Specific Experience on the Perceptual Processing of Letters,” suggests that “perceptual identification of an item is facilitated by recent prior experience with that item” (Sanocki 435). He goes on to argue (based on empirical data) that “perceptual processing is predicted to be more efficient for letters of a single font than for letters from a mixture of fonts” (Sanocki 437). So, via the typography, the title sets us up for some of the disorienting and ambiguous aspects of the film. The difference between the three type fonts (ranging from eloquent to crude) evoke the tension between social classes that will later characterize the complicated relationship between Dr. Murphy and the boy Martin (whom he assumes a parental role with).

The final question that arises from the title is the meaning of the word “sacred” itself. On a basic level, it is certainly a direct allusion to the story of Iphigenia and Artemis’ sacred deer that was killed.

But what makes the metaphorical deer “sacred” in this film?

If we use the allusion to Euripides’ text, the killing of the sacred deer which forces the act of the eventual sacrifice happens before the main action of the play. In the film, this would imply that the sacred deer is Martin’s father who died at the hands of Dr. Murphy in surgery. But why is Martin’s father sacred? Why isn’t he just another victim of Dr. Murphy’s neglect? Girard offers a paradoxical explanation: “Because the victim is sacred, it is criminal to kill him–but the victim is sacred only because he is to be killed” (Girard 1). Using this idea, Martin’s father only becomes sacred (and thus the killing becomes significant) after the killing has taken place–retroactively. In this interpretation, it is not the doctors who are acting as the deity figures but Martin himself. This provides a possible explanation for the curse and Martin’s seemingly supernatural vision and abilities.

One of the Oxford English Dictionary definitions for “sacred” is: “consecrated to; esteemed especially dear or acceptable to a deity” (OED). Martin’s father is dear to Martin because he is his father. So, the predication of him taking on the “sacred” adjective is due to intra-familial ties, a theme that is crucial in the final sacrificial scene when Dr. Murphy kills his son, Bob, further suggesting that Bob could also take on the symbolic role of the sacred deer. Like in Iphigenia At Aulis, the “deer” killing sets off the chain of events that are impossible to stop without the sacrificing of a family member. In this film, Lanthimos creates a similar (perhaps more extreme) cause and effect relationship between the two sacrificial acts. Dr. Murphy must kill a member of his own family because he killed a member of Martin’s family and that is the only possibility of balance.

detachment and disgust

The shot that immediately follows the title is another aerial (god) shot that is positioned over a trash can. Dr. Murphy takes off his scrubs and bloody gloves post-surgery and haphazardly tosses them into the trash can as the camera zooms in. The way in which Dr. Murphy removes his gear hints at his apathetic composure and lack of acceptance throughout the film. His detachment from the preceding tragic event implies a detachment from reality and inability to take responsibility for his actions. Ahmet Yuce, in his essay “Between Phenomenology and Poststructuralism: The Medical Gaze in Crisis in The Killing of a Sacred Deer”, points out the importance of the latex gloves. He acknowledges that Dr. Murphy’s hands are covered from actually touching the heart while operating on it, suggesting detachment. This detachment is repeated throughout the narrative and reflects itself in Dr. Murphy’s character arc (which is almost non-existent). Dr. Murphy never moves to a place of remorse. He never accepts blame and apologizes for what he has done. He becomes more melancholy throughout the course of the film but his sadness is directed toward his own disturbing situation, not Martin’s. Instead of empathizing with Martin he kidnaps and tortures him. His inability to face his guilt is essential to his punishment but it also destroys any sympathy we feel for him. Our identification with Dr. Murphy’s character is thus problematized by his lack of regret and apology regarding the death of Martin’s father. This is a potential failure of the film when working as a tragedy. The audience is not allowed to experience the feelings of pity and fear (and eventual catharsis) because our identification with Dr. Murphy as the protagonist is perpetuated only with apathy and disgust.

The temporal location of this entire opening segment within the narrative is brought into question by the editing and placement within the film. When we later learn of the failed surgery of Martin’s father, we assume that this opening scene is depicting that event. However, we are never given any actual indication of that being the case. The only shot of the heart is of it beating; we never see it dead. The sullen and detached expression on Dr. Murphy’s face (combined with the deliberate use of slow-motion) implies some sort of failure. However, he maintains that near-exact expression in almost every scene of the movie, regardless of his emotion. Lanthimos directs the entirety of the film in such a way that makes discerning internal emotion of characters from their facial expressions (and even dialogue) almost impossible. So, it is plausible that the opening scene is not the death of Martin’s father but simply another patient in surgery (it is important to note that Martin never specifically mentions that the surgery was heart surgery). The textual problem that arises out of this unclear temporal placement is that the reliability of Martin’s story and thus the explanation of the supernatural events is brought into question.

The scene immediately after the opening sequence also raises questions about where in the timeline it occurs. This scene (filmed entirely in one shot) uses a dolly shot to track backwards down a hospital hallway while Dr. Murphy and Dr. Williams walk and talk through the hospital. It’s placement within the film suggests it occurs immediately after the surgery. However, despite seeing two people in the surgery room, we never see Dr. William’s face so it is unclear if it is him at that time. This scene could possibly be occurring months after the accident and is closer to the rest of the movie’s events. Regardless of its positioning, the effect of the scene is still the same. As the two walk down the hallway and discuss their watches (the type of band they have, where they got it, how much water resistance it has), the character motif of detachment and disillusionment with reality is on full display. The monotone dialogue used, which is another common motif in the film, perpetuates the banality of not only the doctor’s existence but also their profession. By placing this scene after the failed heart surgery, Lanthimos shows their total lack of emotional investment in what happened. The effect of the one-shot through the long hospital hallway emphasizes how trapped they are within this web of their profession. The white walls and narrow corridor enclose them, pressuring them from every direction, similar to how trapped Dr. Murphy will feel when he realizes there is no other option but to kill a family member. The dialogue in this scene is perhaps the best exemplification of Dr. Murphy’s tragic flaw. It is not the alcoholism that lead to the botched surgery, it is simply his apathy toward the world.

Our modern Tragedy

For Classic Greek Tragedy, Aristotle laid out some of the basic necessary rules that the tragedy must follow for it to be effective: “Tragedy is an imitation not only of a complete action, but of events inspiring fear or pity. Such an effect is best produced when the events come on us by surprise…” (Aristotle). The action of both Iphigenia At Aulis and The Killing of a Sacred Deer is the completed action of the father’s sacrifice of his offspring. In Euripides’ play, the events that inspire fear and pity is the horror of the situation combined with Agamemnon’s surprising and arguably unethical decision to kill his own daughter rather than face the wrath of his own army. The pity and fear within the film is far more internal and takes the conflict within the father to the extreme. For Dr. Murphy, there is no army itching to go to war that holds sway over his decision. His decision, instead, takes a different form. For him, loss will be inevitable, it is simply the extent of that loss and his role in it that arrives in the form of choice for him. This problematizes the modes of pathos the text can use to evoke pity and fear as the inevitability of death somewhat diminishes the final shock of the killing. Instead of the father’s choice evoking the pity and fear, it is more so his lack of choice that potentially increases spectator identification with him in understanding the impossibility of the decision he must make. This is one possible way in which the film evokes pity and fear but this instance, in and of itself, is not as powerful as the original play in that the audience also blames Dr. Murphy for his actions and the resulting karma.

Aristotle also notes that there should be a “change of fortune” that the hero experiences and that this change “should be not from bad to good, but, reversely from good to bad. It should come about as the result not of vice, but of some great error or frailty…” (Aristotle). Again, Dr. Murphy lacks a specific tragic flaw that can be acknowledged as the reason for these events (his alcoholism or general apathy are certainly elements that contribute to a character flaw but don’t hold enough sway or attention in the narrative to dictate the deciding factors of the tragedy). His error occurs temporally much earlier than the narrative we are shown; the killing of Martin’s father is not a part of the film’s plot structure/arc. So, while Dr. Murphy’s change of fortune certainly moves from good to bad throughout the course of the film, the intentional framing that omits the tragic error prevents the audience from witnessing the moment of initial choice. The way in which the film is presented thus makes Dr. Murphy’s story one of inevitability and fate, rather than free-will since his previous actions has cost him the luxury of free-will.

Another way to examine the course of events and the character decisions made by Dr. Murphy is to frame them through the act of revenge. There are two major acts of revenge in the film: the first is Martin (as connected to a supernatural force) taking revenge on Dr. Murphy for killing his father and the second is Dr. Murphy taking revenge on Martin by kidnapping and torturing him. The first act of revenge is strange because of Martin’s detachment from it. The film never draws a distinct connection between the “curse” and Martin himself and it is unclear if he is directly (by his own hand) causing the horrible effects on the family. There are several moments where he specifically mentions that there is nothing he can do about it; that it is out of his hands completely. This suggests that the first act of revenge is not on a human level but on a universal/supernatural level. There is no need for human intervention with this type of revenge–it is simply nature balancing things out. This fact makes the second act of revenge more destructive and more significant as Dr. Murphy attempts to intervene in the natural balance and take matters into his own hands.

Both forms of revenge follow a path that is outside the societal boundaries of law. Sir Francis Bacon discusses this kind of revenge, writing, “The most tolerable sort of revenge is for those wrongs which there is no law to remedy…” (Bacon 348). It is clear that the law did not provide any kind of remedy for the murder of Martin’s father because Dr. Murphy is still a practicing doctor and Martin appears to be the only one who has suffered. The law would also be incapable of remedying Martin’s curse because of its supernatural and ambiguous qualities. In this way, both forms of revenge appear to be similarly just in terms of their intent. However, they diverge on a crucial point that Bacon makes about the nature of a vengeful act: “…the delight seemeth to be not so much in doing the hurt as in making the party repent” (Bacon 348). In the first case, Martin takes no delight in the pain (and often appears uncomfortable when discussing it). However, Dr. Murphy certainly enjoys torturing Martin as he frequently abuses him when Martin has no power in the matter. In both instances, repentance is impossible because it is in the hands of nature, where no human intervention has any effect.

These constructions of revenge and the tragic flaw mark some interesting comparisons between modern and classical forms of tragedy.

The “supernatural” force in Iphigenia At Aulis has the same amount of power as the one in the film but takes on a more explained position as the goddess of Artemis. Just as the killing of Artemis’ sacred deer cannot be rectified by any means other than the sacrifice that she demands, the killing of Martin’s father can only be repaid by the familial sacrifice at the hands of Dr. Murphy. In a sense, the supernaturalism in The Killing of a Sacred Deer evokes this kind of mythic presence from the ancient world that is otherwise absent in modern life and storytelling. In his essay, “Tragedy, Realism, Skepticism,” Benjamin Mangrum explores this connection between both the ancient and modern forms of tragedy, saying: “Tragedy is neither friend nor foe in modernity. It can as easily be a generic vehicle for the forms of violent conflict in modernity as it can express a classical worldview that predates the rise of capitalism and liberal humanism” (Mangrum 216). The shocking and disorienting violence and violent repressions present in the film can also act as a way to represent a more classical idea of tragedy. The fact that it is so shocking is because it is an ancient societal form placed in a modern context. This blending of ideas is one of the greatest strengths of the film.

Mangrum continues to argue the differences between classical tragedy and ‘realist’ modernism, presenting juxtapositions between the two. He argues that modern writing “narrativizes middle-class values, whereas tragedies stage the fall of aristocratic or ‘great’ houses” and that while modern stories evoke a “realist or secular view of history,” tragedies “enfold human agency within the forces of divine fate” (Mangrum 209-210). Lanthimos’ tragedy is structured entirely around the blurring of these lines. While the Murphy family attains a higher status than “middle class,” they are certainly not a “great house” or so wealthy to be considered some kind of modern aristocracy. The curse also provides a kind of divine element within a deeply secular (and cynical) world, making it all the more out of place. The line between morality is perhaps the most important line that is blurred. Hegel points out the “false notion of guilt or innocence in tragedy, suggesting that “the heroes of tragedy are quite as much under one category as the other” (Hegel 70). Dr. Murphy wants to protect his family that he repeatedly insists that he loves, yet he also frequently ignores him and the curse becomes more about his suffering than theirs. These blurring of lines are, quite possibly, the only way to adapt an ancient tragedy like Iphigenia At Aulis into a modern setting because of the fact that our societies are so different. However, the violence prevalent in the film adaption possibly suggests that our relationship with violence as a culture has changed little.

Kim, Bob, & Iphigenia

The second major scene within the film that I would like to analyze is the moment when Kim (the daughter) accepts the reality of the situation and begs her father to kill her so that she can be the one to save the family. This scene is the most direct connection to Iphigenia At Aulis, reflecting the scene where Iphigenia decides to accept her fate and sacrifice herself. Naomi Weiss, in her essay “The Antiphonal Ending of Euripides’s ‘Iphigenia in Aulis,’” suggests that while most of the play is focused on the character of Agamemnon, “in the last third of the play […] the gaze of both the audience and the characters within the play is increasingly directed away from the great army and instead toward the solitary figure of Iphigenia” (Weiss 122). This is reflected in the film scene by the cinematography as the shot opens in a medium shot, close in on the figure of Kim on the bed. As the scene moves on, the stationary camera begins to slowly zoom out, revealing her parents beside her. The narrative is also more reflective of a shift toward the perspective of the other family members in the final third of the movie as well, often prioritizing the dialogue or reaction from either Kim or Bob as opposed to Steven, who becomes increasingly distant.

Another parallel from Iphigenia to Kim is the choice of death itself. Christina Sorum suggests that Iphigenia’s choice is a simple one: “to oppose or embrace her fate. Clearly she is going to die (in fact or in appearance), as either a willing sacrifice or a victim of mob violence” (Sorum 540). Similarly, Kim realizes that Martin is not going to save her (her decision coming after the scene of denial in the basement) and thus acknowledges the inevitability of her death. Here, like Iphigenia, she attempts to choose a nobler end. Kim says of her action: “Kill me right here in front of you and leave me with the ultimate joy of saving my own mother and beloved brother from certain death.” This self-sacrifice is acknowledged by Kim to be a “good” act because it saves the lives of others. On the other hand, Iphigenia’s self-sacrifice is not performed to save the lives of others but to start a war, problematizing the virtue of her decision.

Rene Girard notes that “In Euripides’ Electra, Clytemnestra explains that the sacrifice of her daughter Iphigenia would have been justified had it been performed to save human lives” (Girard 11). Kim’s sacrifice could then possibly be considered more justified than Iphigenia’s. In turn, it is interesting to consider the fact that Agamemnon accepts his daughter’s request while Dr. Murphy does not (and Kim is eventually spared in the end), creating a reversal between the two texts where neither outcome functions as a justified or ethical sacrifice.

The most significant parallel between the two texts is the daughter’s forgiveness of the father and complete acceptance of responsibility. Sorum ties Iphigenia’s decision to an acknowledgement of Agamemnon’s duties, saying that she “perpetuates the patriotic theme introduced by her father in his final attempt to divest himself of responsibility for her death; she maintains his fantasy that his act is justified, that he is not responsible” (Sorum 541). Kim also takes all of the responsibility and works to absolve her father completely. She tells him this even more directly that Iphigenia, saying things like “let me be the one who atones for your sins, Dad” and “I would do anything for you. I would even die for you and here’s my chance to prove it.”

This “sheltering” of the father is part of the lack of his ability to grow as a character throughout the story. He waits out the period of his family’s suffering until they get to the point where the only option they have left is to do anything to appease him. Kim even goes to the point of saying, “you gave me life and you, only you, have the right to take my life away.” In denying him the moment of acceptance and repentance, Kim prolongs the myth (in Steven’s mind) that he is innocent and therefore has no possible action he can take himself.

The Sacrifice

The final scene I will discuss is the climax of the film: the sacrificial scene.

Here, Dr. Murphy ties up each member of the family and places them in a triangle of chairs in the living room. He proceeds to place bags over each person’s head so they are unable to see. He then picks up a rifle, covers his own face, and spins around the room until he finally shoots. He does this three times, missing twice before finally shooting Bob. The very methods of preparation and action that Dr. Murphy take in this scene evoke something highly ritualistic, implying that this is a kind of ritual sacrifice. Even Anna, before she goes downstairs, tells Steven that she is going to wear the fancy dress that he likes: she is preparing in dress for an event of importance. The faith that Dr. Murphy has placed in the supernatural curse has, by this point, reached its totality. He performs the act in a ritualistic manner partially because he understands its importance but also because he now fully believes in it.

It is also significant that Bob is the one who is killed. The filmmaking and narrative up to this point suggests that, despite the sacrifice being performed as a random act, Bob (via fate) is the one who has to die. Not only is Bob the first family member who feels the effects of the curse but he is also the only family member to never accept his fate. Kim offers herself up to be sacrificed in the scene previously discussed and just after that scene, Anna lets Martin leave, telling Steven that there was no resolution available from keeping him around and thus accepts the inevitability of death. Bob is the only one who refuses until the very end. He cuts his hair in the hope of appeasing his father but it is only to be spared. This is literally reflected in the sacrificial scene as Bob is the only person who struggles against his father as he puts the bag over his head. Not being willing to sacrifice himself, Bob ironically necessitates the end result of his death. This further reinforces the theme that free-will within the family has ceased to exist and there is a decided fate that has already determined the course of the events, regardless of what the family chooses.

Another element to why Bob was the one who must die ties into the idea of cyclical vengeance. Bob, being the only other male in the family, is the closest character to being like Steven. Bob even mentions at one point that when he grows up he wants to be a cardiologist like his dad, saying that he prefers it to his mother’s job. Girard notes that “there is the risk that the act of vengeance will initiate a chain reaction whose consequences will quickly prove fatal to any society of modest sizes” (Girard 15). If we continue using the theory that the first act of vengeance was performed as a balancing of nature, then the death of Bob is the final moment of that balancing. If Bob survived, then he is the most likely member of the family to follow in his father’s footsteps, even going into his same line of work and perpetuating this cyclical process that Girard argues the act of sacrifice works to prevent.

There is no greater symbol of the death of free will in the film than the image of Steven Murphy spinning around his living room blindfolded with a rifle. By making the act of sacrifice random, he is leaving everything up to fate. The film is littered with examples of Dr. Murphy’s inability to make decisions, the central one being which family member to kill. He goes to the extreme of visiting his children’s school principal and blatantly asking which child is “better”. Herbert Siegel in his essay, “Agamemnon in Euripides’ ‘Iphigenia At Aulis,’” points out that “fear and powerlessness are traits which seem to arise continually in Euripides’ portrayal of Agamemnon” (Siegel 263). The inability to choose is itself a major structuring device within Euripides’ text (i.e. the letters, deception) and the same thing can be found in Lanthimos’ film. Sorum also notes of tragedy that “unless people are free and responsible agents, human action has insufficient meaning to be a subject of tragedy” (Sorum 528). Again, with the non-linearization of the plot, the action of choice has been performed before the events of the film and Dr. Murphy’s ability to choose slowly dwindles over the course of the story. In an ironic twist, he has lost choice in life by choosing to kill. The final sacrificial scene is Dr. Murphy’s final, desperate attempt at regaining some choice via agency and being the person to pull the trigger. Yet, it doesn’t really matter due to fate’s intervention and the blindfolds he has placed upon everyone.

Of all the characters in the film, Dr. Murphy is the most pessimistic and the most detached from reality. Not only does this create spectator identification issues but it also problematizes the tragedy’s effectiveness in evoking pity and fear. John Von Szeliski argues that this is a major problem with modern tragedy and the modern tragic hero. “The death-wish is alarmingly popular in the chief characters of modern American tragedy. […] The modern tragedy simply does not display in its characters a strong will for life…” (Szeliski 40). Based on Szeliski’s definitions, Dr. Murphy fits very well under this category of the pessimistic modern tragic hero. Of all the characters, he is the one who welcomes death the most. He talks about material things and private matters with little attention to whom he says them to or their reaction. His monotone delivery of dialogue suggests a near complete detachment from others and even from himself. When the children get sick, he doesn’t act rationally but tries to “force” them to get better. It is ironic that he is the only character who wants to die, yet he is the only character who is not given that option.

Szeliski continues on to say that “the pessimistic character has so little respect and admiration for what he sees around him and what he sees in himself that it is impossible for us to make a tragic identification…” (Szeliski 43). This is where the film differs again from Euripides’ play and where it is less effective: through the father character. The audience feels pity for Agamemnon (despite whether or not we believe in his morality) because he is extremely invested in the choice he has to make and has a lot to lose either way. Dr. Murphy is already so apathetic toward the world and emotionally detached from his family that the audience never really reaches a point where we feel sorry for him. There are even moments, in his angry outburst, that the audience can find ways to actively root against him, understanding that his punishment is just. At one point Dr. Murphy insistently tells Anna that “a surgeon never kills a patient. An anesthesiologist can kill a patient, but a surgeon never can.” This shows a lack of acceptance for his own moral actions and his refusal to take blame. This is also why he has no character arc: he is the same at the beginning of the film as he is at the end. There is never a moment where he empathizes with Martin and feels remorse for his actions. He feels sorry about his family, but the only thing he ever feels toward Martin is anger, even in the final scene as he ignores him in the diner. Hegel argues that the destruction of the hero is necessary in any tragedy for the proper effect to work on the audience. In this film, the destruction of the hero does not occur and there is no ethical conclusion to the tragedy; there is only more violence.

Yorgos Lanthimos’ 2017 film The Killing of a Sacred Deer offers many scenes that directly correspond to Euripides’ Iphigenia At Aulis. However, there are several crucial differences that problematize the traditional notion of sacrifice and the tragic character via ambiguous sacrificial rituals, character identification, and the moral ambiguity of high-class professionals within society. Rene Girard argues that “the purpose of sacrifice is to restore harmony to the community, to reinforce the social fabric” (Girard 8). Like with Agamemnon and Iphigenia, Dr. Murphy must sacrifice a family member in order to restore societal balance and good relations between humanity and the unexplained deity figures. However, his apathy toward his actions and his denial of the consequences prevents any catharsis to be reached by the end of the film and leaves the narrative primed for a dangerously cyclical pattern of societal violence, perpetrated without consequence by society’s elites.

Works Cited

Alexiou, Margaret. "Reappropriating Greek Sacrifice: homo necans or άνθρωπος θυσιάζων?" Journal of Modern Greek Studies, vol. 8 no. 1, 1990, p. 97-123. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/mgs.2010.0352.

Aristotle. “Poetics.” Translated by S H Butcher, The Internet Classics Archive, Web Atomics, http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/poetics.1.1.html.

Budelmann, Felix, and Pat Easterling. “Reading Minds in Greek Tragedy.” Greece & Rome, vol. 57, no. 2, Oct. 2010, pp. 289–303. JSTOR, https://www-jstor-org.unco.idm.oclc.org/stable/40929480

Comanducci, Carlo. 2017. “Empty Gestures: Mimesis and Subjection in the Cinema of Yorgos Lanthimos.” Mise en geste. Studies of Gesture in Cinema and Art (ed. by Ana Hedberg Olenina and Irina Schulzki). Special issue of Apparatus. Film, Media and Digital Cultures in Central and Eastern Europe 5. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17892/app.2017.0005.56

Eliot, Charles W. The Harvard Classics: The Shelf of Fiction: Francis Bacon. P. F. Collier and Son, 1909. Bartleby, https://www.bartleby.com/3/1/4.html.

Elsaesser, Thomas, and Malte Hagener. Film Theory: an Introduction through the Senses. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2015.

Euripides. Iphigenia At Aulis. The Internet Classics Archive, http://classics.mit.edu/Euripides/iphi_aul.html.

Finlayson, James Gordon. "Conflict and Reconciliation in Hegel's Theory of the Tragic." Journal of the History of Philosophy, vol. 37 no. 3, 1999, p. 493-520. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/hph.2008.0809.

Foley, Helene P. Ritual Irony: Poetry and Sacrifice in Euripides. Cornell University Press, 1985. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctvn1tb8f.6?seq=4#metadata_info_tab_contents.

Girard, René. Violence and the Sacred. 1st ed., Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979.

Lanthimos, Yorgos, director. The Killing of a Sacred Deer. 20th Century Fox, 2017.

Lush, Brian V. "Popular Authority in Euripides’ Iphigenia in Aulis." American Journal of Philology, vol. 136 no. 2, 2015, p. 207-242. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/ajp.2015.0032.

Mangrum, Benjamin. “Tragedy, Realism, Skepticism.” Genre: Forms of Discourse and Culture, vol. 51, no. 3, 1 Dec. 2018, pp. 209–236. Duke University Press, https://doi-org.unco.idm.oclc.org/10.1215/00166928-7190493.

"sacred, adj. and n." OED Online, Oxford University Press, September 2019, www.oed.com/view/Entry/169556. Accessed 9 November 2019.

Sanocki, Thomas. “Effects of Font- and Letter-Specific Experience on the Perceptual Processing of Letters.” The American Journal of Psychology, vol. 105, no. 3, 1992, pp. 435–458. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1423197.

Siegel, Herbert. “Agamemnon in Euripides' 'Iphigenia at Aulis'.” Hermes, vol. 109, no. 3, 1981, pp. 257–265. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4476212.

Sorum, Christina E. “Myth, Choice, and Meaning in Euripides' Iphigenia at Aulis.” The American Journal of Philology, vol. 113, no. 4, 1992, pp. 527–542. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/295538.

Von Szeliski, John. “Pessimism and Modern Tragedy.” Educational Theatre Journal, vol. 16, no. 1, Mar. 1964, pp. 40–46. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3204376.

Weiss, Naomi A. “The Antiphonal Ending of Euripides’ Iphigenia in Aulis (1475– 1532).” Classical Philology, vol. 109, no. 2, Apr. 2014, pp. 119–129. JSTOR, doi:10.1086/675252.

Yuce, Ahmet. “Between Phenomenology and Poststructuralism: The Medical Gaze in Crisis in The Killing of a Sacred Deer.” Film Philosophy Conference, 2018. Semantic Scholar, https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Between-Phenomenology-and-Poststructuralism:-The-in-Yuce/69bd7cf3f8b609075ac93c7bc6e27f891eaff843.

Social

Leave a Comment